21

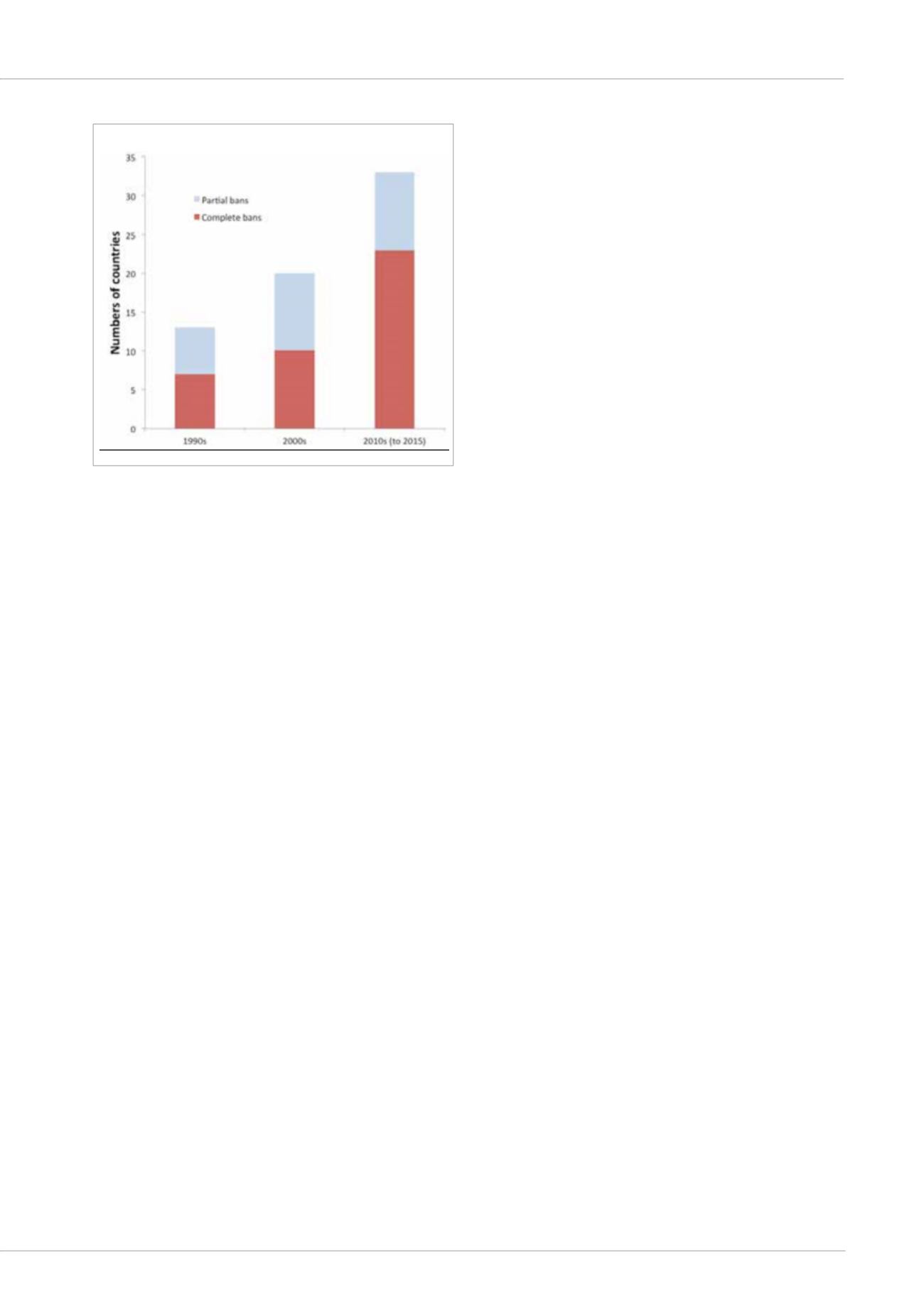

Figure 2:

Progress towards eliminating the use of lead gunshot

in wetlands world-wide.

Partial bans include situations where some

progress has been made but a complete national ban has yet to be

achieved. Data from Fawcett and van Vessem (1995), Kuivenhoven and

Van Vessem (1997), Beintema (2004), and AEWA (2015).

CONCLUSIONS

As with many other pollutants, the regulation of lead in the

environment has typically lagged (many) decades after the

recognition of its impacts, whether to the health of humans or

wildlife. Indeed, leaded paint and leaded petrol remains in use

in some countries over a century after the recognition of the

toxicity of the former and

c.

80 years after the appreciation of

TEL toxicity. Exposure to lead from multiple sources continues

despite recognition of the problem at the highest levels.

The Governing Council of the United Nations Environment

Programme adopted a decision in 2003 in which it:

“ 6. Appeals toGovernments, intergovernmental organizations,

non-governmental organizations and civil society to

participate actively in assisting national Governments in their

efforts to prevent and phase out sources of human exposure to

lead, in particular the use of lead in gasoline, and to strengthen

monitoring and surveillance efforts as well as treatment of

lead poisoning, by making available information, technical

assistance, capacity-building, and funding to developing

countries and countries with economies in transition.”

(UNEP 2003)

The development of regulations to address pollution that has

health or environmental impacts, especially when industrially-

derived, has always been problematic. This has typically led to

‘late lessons from early warnings’ as explored in detail by EEA

(2001, 2013).

Development and acceptance of better, risk-reducing,

regulations typically face two impediments to change: the

opposition of vested interests (typically economic and/or

political, as described by Michaels (2008) and Oreskes and

Conway (2010)), and a reluctance to accept the need for change

by stakeholders or wider society – often resulting in the failure of

voluntary approaches to encourage change.

The role of economic interests in slowing the development and

implementation of better regulation has been documented in

many of the sources given in this paper but, perhaps typically,

Wilson and Horrocks (2008) gives a detailed assessment of the

multiple factors which long-delayed the removal of lead from

New Zealand’s petrol.

In some situations, public can readily embrace the need for

better regulation. Thus Wilson (1983) documents the campaign

to remove lead from petrol in the UK which, in 1983, had a

massive cross-section of British civil society aligned against

the government, the petroleum and lead industries, and car

manufacturers. Yet in other situations, such as the encouraged

voluntary phase-outs of lead fishing weights in the 1980s and

of lead gunshot over wetlands in the 1990s, stakeholders have

resisted change. Such response has an extensive sociological

literature, especially in the context of climate change denialism

(

e.g.

McCright and Dunlap 2011, Washington and Cook 2011).

Cromie

et al.

(2015) reviews the issue further in the context of the

continuing high levels of non-compliance with UK lead gunshot

regulations.

Several common themes emerge from the history of removal

of lead in petrol (Table 3). Many types of argument used by

industrial advocates of leaded petrol in the 1960s and 1970s

are not dissimilar to those currently adopted today against the

change away from toxic lead ammunition.

Regulation of some sources of lead poisoning